Why the overload meltdowns after school?

Because you’re their safe place.

When they get home, school-aged children may have spent close to 7 hours in intense activity from the moment they left home. What about you? How do you feel after a long workday?

Imagine spending the day with someone giving you instructions that are difficult to follow for tasks and projects you don’t understand in a noisy and visually overwhelming environment…

Wouldn’t you collapse when you get home?

One parent said it very well [1]:

“See, when our kids hold it together all day long at school for their teachers, they come home and they’ve lost every bit of control they had.

They’re finally in a space where they don’t have to keep it together, so they lose it.

You’re their safe place.”

If you would like, you can skip the explanations about sensory overload, the pressure to perform and stress and go straight to the 6 steps to relieve after-school overload

Stress and overload at school

Over 90% of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) demonstrate atypical sensory behaviors [2]. Additionally, findings estimate that 16% of the general population have sensory processing difficulties [3].

Consider the following examples of irritating and persistent sounds, lights and textures that our children with sensory processing challenges may face at school.

Sensory overload

- Auditory overload:

- Constant noise from the voices of the people around him

- Ear piercing bells

- Chairs moving

- Scratching of pens

- Neon lights buzzing

- Noise from outside

- Complete silence can sometimes be anxiety-producing as well

- Visual overload:

- Flickering lights

- Hyper-decorated walls

- Aggressive colors and patterns on the floors, the walls

- Aggressive colors and patterns on other people’s clothes

- Tactile overload

- The clothes he is wearing

- The irregular texture of a cheap pencil

- The bumps on the chair

This video highlights autism advocate Carly Fleischmann who is non-verbal and on the autism spectrum. In this video simulation Carly is with her family in a crowded coffee shop and the anxiety that it can lead to.

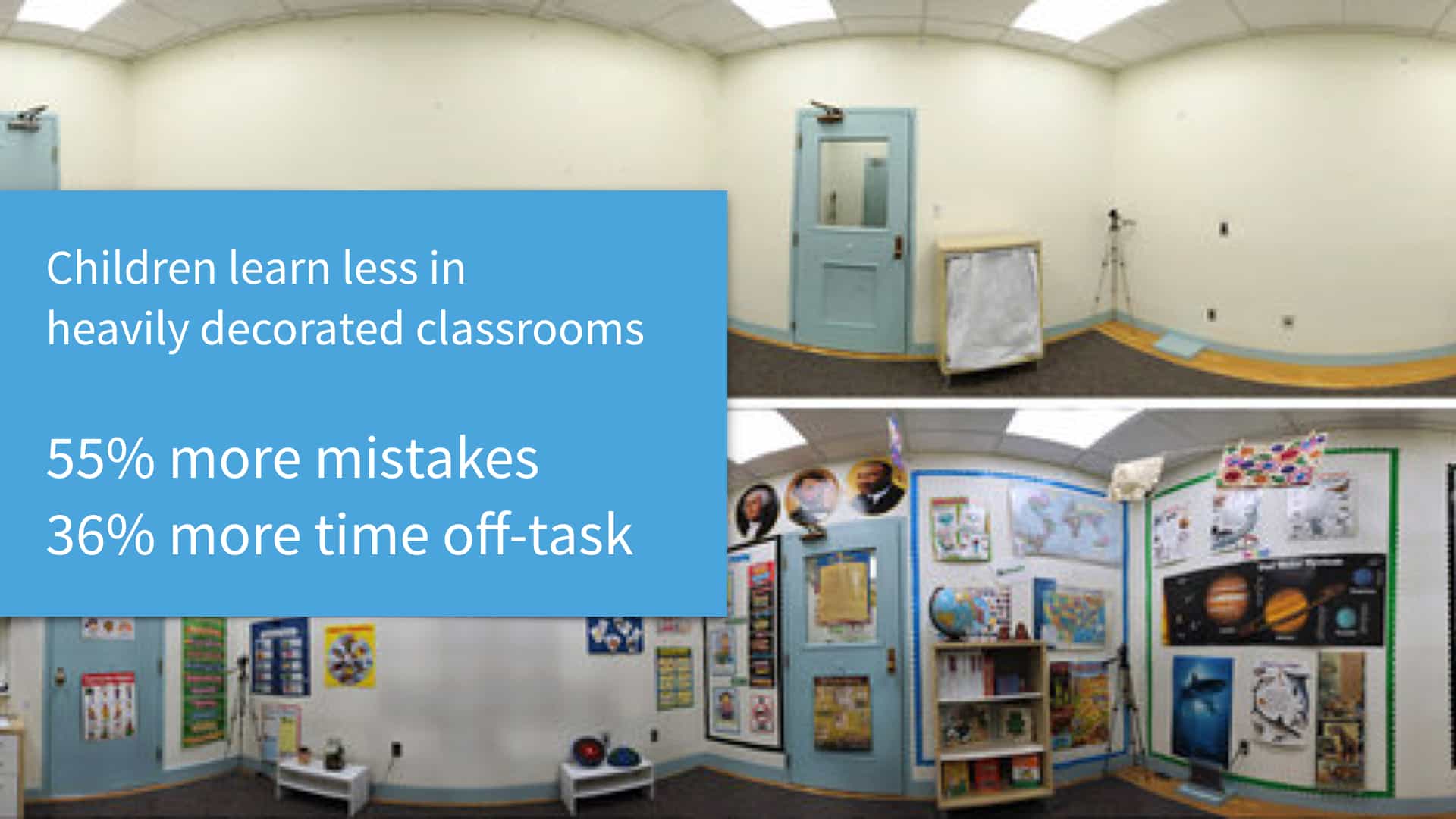

Psychology researchers looked at whether visuals and displays in a classroom affected children’s ability to maintain focus and to learn the lesson content [4]. They found that children in highly decorated classrooms, compared to children in sparsely decorated classrooms, were:

- more distracted,

- spent 36% more time off-task

and - made 55% more mistakes

Beyond learning difficulties, the overwhelming sensory stimulation in the classroom bombards the child’s brain and causes confusion, headache and distress.

It does not take long for the sensitive child to reach a level of distress than is no longer bearable.

While the sounds can artificially be decreased by the wearing of noise cancellation headphones, the child cannot be inside the classroom and protect himself from the visual stimulation except by closing his eyes, unless schools take measures to re-think the way they decorate classrooms.

Pressure to perform

At school, children are required to do a lot of things in a high pressure environment both academically and socially and this is another area where stress mounts for our children.

Answering questions and participating can be challenging enough, but have you thought of the demands to stay motionless and quiet? For a variety of reasons (hyperactivity, misunderstanding of social cues, anxiety,…) many of the children on the spectrum have difficulties sitting still.

Transitions are a large part of any school or work day, as we move to different activities or locations. Studies have indicated that up to 25% of a school day [5] may be spent engaged in transition activities, such as:

- moving from classroom to classroom,

- coming in from the playground,

- going to the cafeteria,

- putting personal items in designated locations like lockers or cubbies, and

- gathering needed materials to start working.

What is interesting, is that adults too find themselves transitioning for a large portion of our day, whether at work or at home.

What is Stress?

Stress is a response by the body to a change in the environment that the body feels is a possible threat. It could be as benign as when you just remembered your wedding anniversary or as severe as a dog chasing you.

Stress can be positive. The human body is designed to deal with stress.

When the body deals with a stressful situation, the brain triggers a release of cortisol to help us stay alert, motivated, and ready to avoid danger. Cortisol can also make us run faster and lift heavier things.

All of this is good, but what is meant to be a temporary boost comes at a cost and when cortisol levels are too high for too long, this hormone can:

- Cause weight gain and high blood pressure [6],

- Disrupt sleep [7],

- Negatively impact mood [8],

- Reduce your energy levels [9],

- Contribute to diabetes [10],

- Disrupt your immune system [11],

- Lead to reduced muscle mass [12],

- Disrupt digestion [13],

- Increase your risk factors for depression [14],

and - Increase pain threshold [15]

Neurologically, long term stress can also lead to:

- Depletion of Serotonin [14],

- Decrease of number of dendrites [16],

- Decrease of neurogenesis in the hippocampus [17],

- Learning difficulties and memory loss [18],

- Alteration of the dendritic morphology of a major population of neurons [19], and

- Reduced growth hormone, testosterone, DHEA and oestrogen output [20]

This leads to the first thing you want to do when your child gets home from school, or when your partner comes home from work: Reduce his stress response.

We’re going to show you how to do that.

6 Steps to Help Them Feel Relief at Home Instead of Releasing All Their Tension on the Family

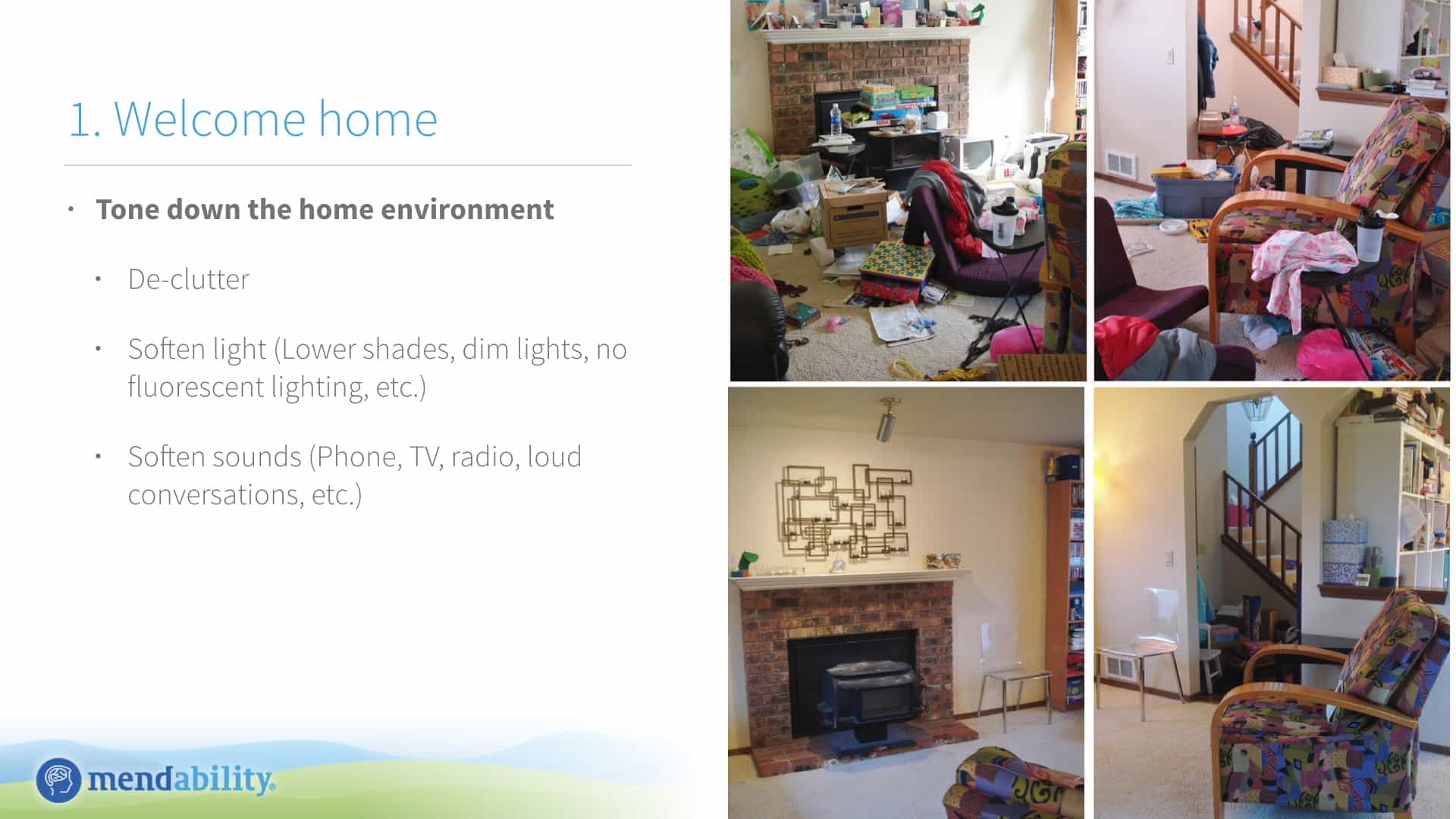

Step 1: Welcome Home

Tone down the home environment:

- Declutter [21]

- Soften light (Lower shades, dim lights, no fluorescent lighting, etc.)

- Soften sounds (Phone, TV, radio, loud conversations, etc.)

Step 2. Quick “Brain Reboot”

Welcome your child with strawberry and ice protocol as he is taking off shoes and coat.

Strawberry and Ice Protocol

- Ice: will present the body with a danger signal for the brain to focus its attention [22,23].

- Strawberry: Processing a scent has a strong interrupt effect on the brain [24]. It doesn’t really matter which scent you use. Scents are processed differently depending on the individual [25,26]. Younger children tend to prefer basic, sweeter, food-related odors [27]. Some studies suggest that strawberry, vanilla and jasmine might be processed differently than most other odors in the brain with higher stimulation of the amygdala, the mood regulation center in the brain [28–30]. Our experience has shown this too. Any pleasant scent will help elevate the mood of the person, with a release of dopamine and Serotonin [31].

- Ice + Strawberry: compound together to provide the brain with an effective “reboot.”

Note: you can use this protocol anytime there is a high stress situation and you want to provide them with instant relief.

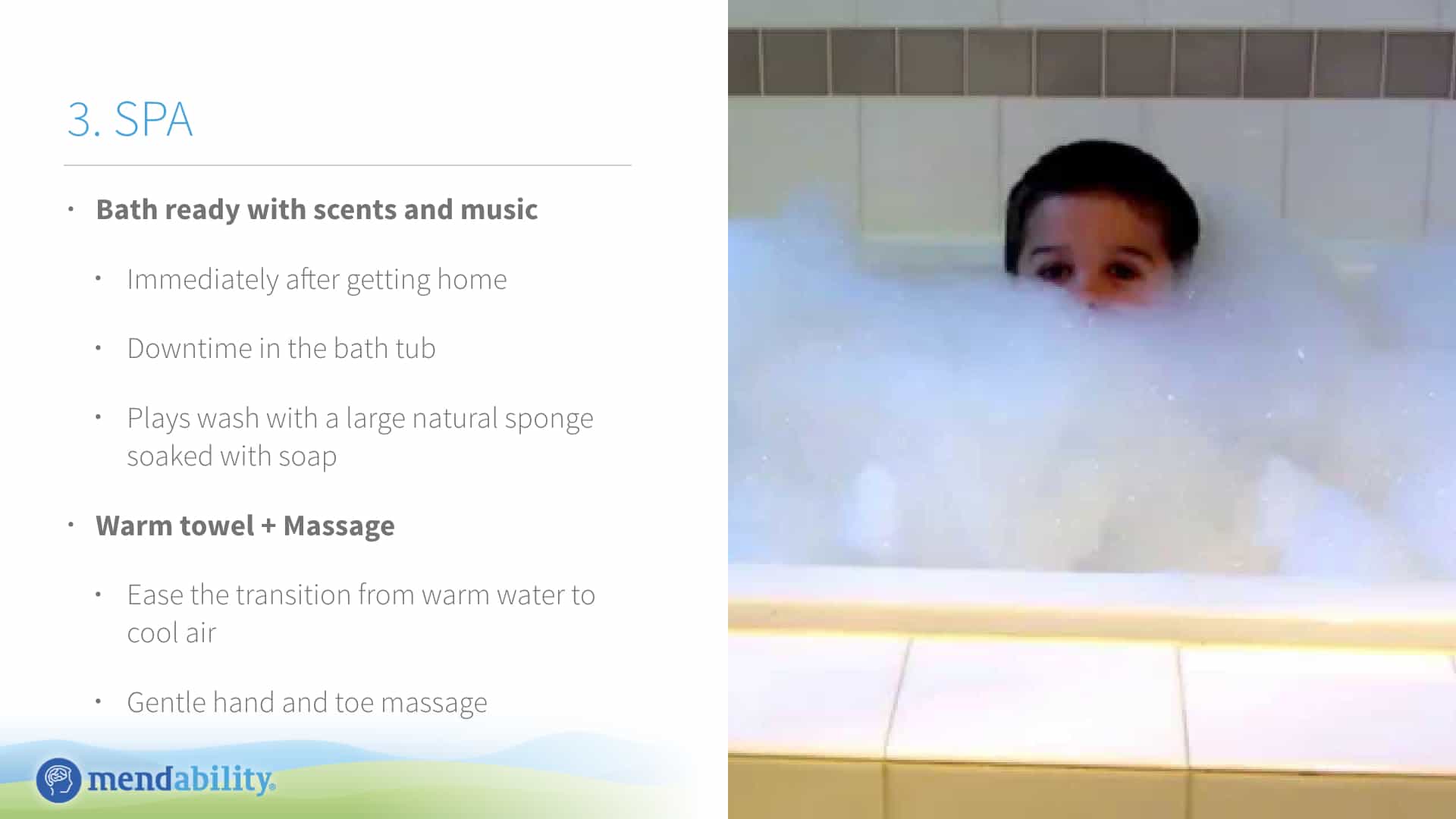

Step 3. SPA

Once your person has been welcomed into a toned-down home environment and you have done a quick brain reboot, it is time to give them a chance to unwind. One of the most powerful combinations of activities that will help the brain unwind can be found in what we call the SPA protocol, which includes:

- Warm bath with scents and music

- Relaxes heartbeat, breathing and muscle tension

- Regulate Serotonin through body temperature regulation (Lowry et al. 2009),

- Pleasant scents help with mood, memory and motivation

- Increase in Serotonin helps with relaxation

- Downtime in the bathtub

- Give him a large natural sponge soaked with soap and let them play “wash”

When your person is ready to get out of the bathtub, wrap them up in a warm towel

- Warm towel + Massage

- Ease the transition from warm water to cool air

- Gentle hand and toe massage to boost Serotonin and increase a feeling of calm

Step 4. Snack

- Be creative with the presentation

- Touch and Smell pairing at the same time

- Soft touch increases serotonin function

- Smell improves serotonin and dopamine

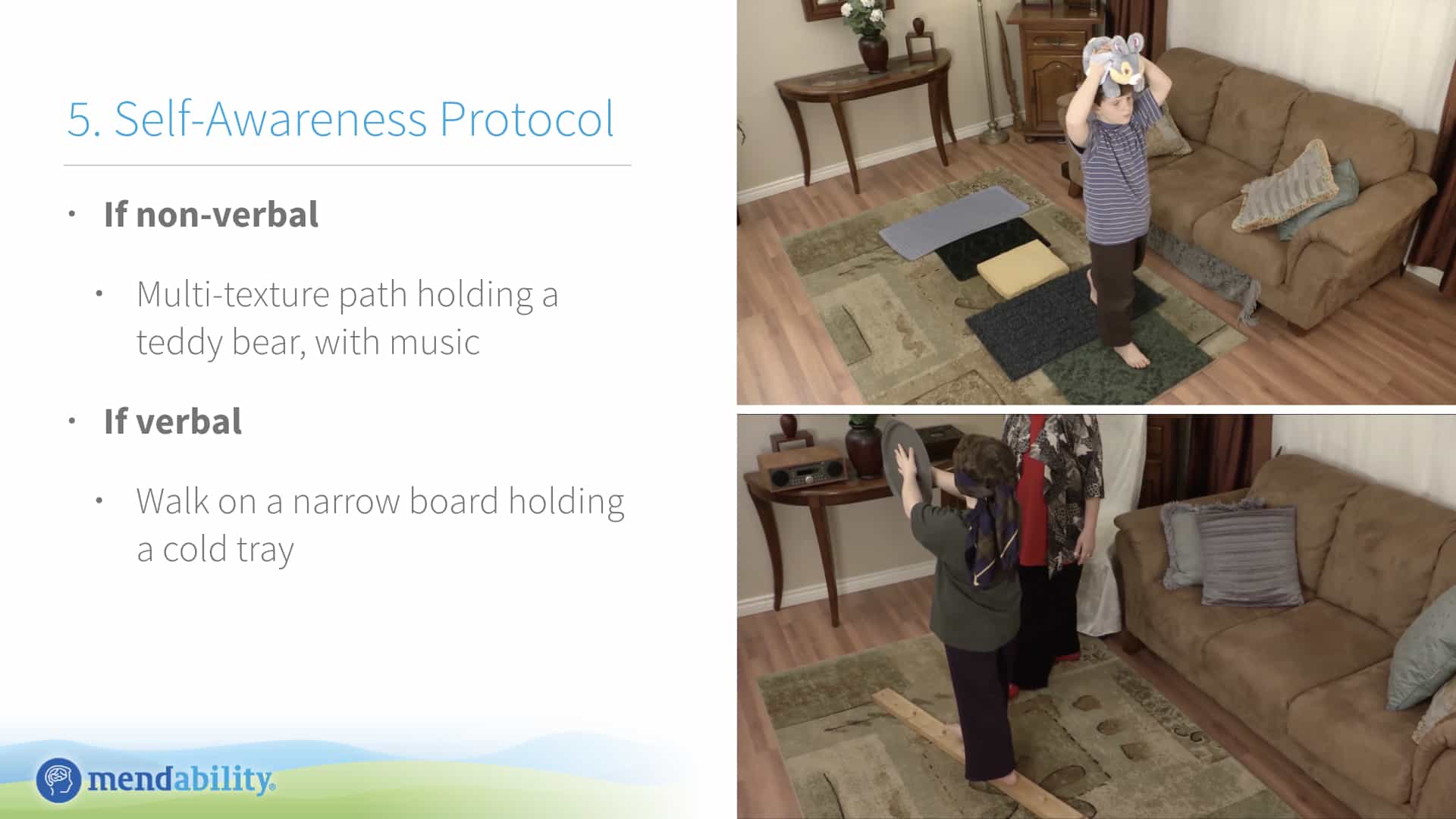

Step 5. Self-awareness Protocol

Now that your person has released all the tension that they accumulated during the day, we are going to do an exercise that will help increase focus and awareness.

After doing the protocols, your person will be ready to tackle challenges for the rest of the day, like homework if this a school-aged child.

If non-verbal: Multi-texture path holding a teddy bear, with music

This exercise requires the person to walk barefoot on a line of different textured surfaces. This is done while holding a teddy bear above his head.

By holding the teddy bear above his head, they will not be able to use their arms to balance. They will also have to re-adjust how they walk and focus on body positioning with each new texture they steps on.

We don’t typically walk on different textures with each foot step. This novel sensation will prompt the brain to focus on the information coming from the feet.

This exercise not only helps with tactile processing, but also with building a stronger mental

awareness of self.

As that information makes its way along the longest neuronal pathway in the body, some good things will happen, like an increase in self-awareness to maintain safety, by doing things like adjust posture and gait.

As explained by researchers at Vanderbilt University, “Perceived body ownership and self-other relation are foundational for development of self-awareness, imitation, and empathy.”

There is also going to be an uptick in Serotonin and the creation of new connections in the brain to process these new sensations from the environment.

All you did was provide a new way of experiencing the environment.

If verbal: Walk on a narrow board holding a cold tray

In the 2X4 we also request a very different way of walking, a foot in front of each other. As is the case in the multitexture path, this causes the brain to focus on body positioning and adjust posture, gait and speed.

The position of the arms would naturally be on the sides to maintain balance. We remove this tool and spontaneous posture with either arms up or in front, which we are not used to do and is in fact quite difficult.

The 2X4 has another difficult part to it, the holding of a metal cold tray vertically by pressure of the palms.

the two exercises request that the brain focus strongly on several functions and give the child a high focus which can be used for handling challenges, if there is homework, or simply play and have fun.

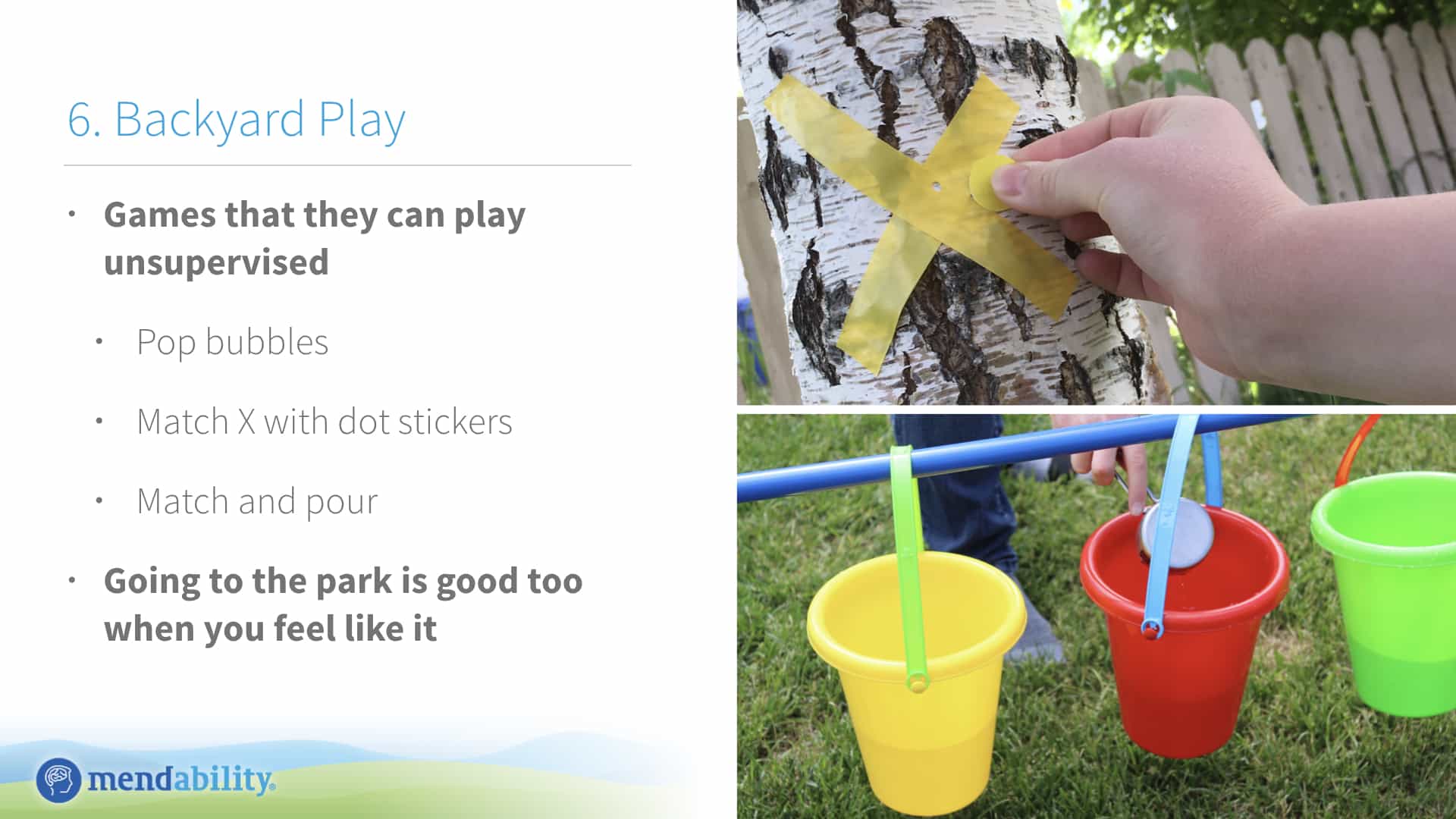

Step 6. Backyard Play

At this point, your person is ready to face challenges like homework, but if they just need to have fun, we have a few ideas for you. Going to the park is also good, but it requires more work on your part.

Here are some examples of backyard games that your person can do with little supervision:

Is behavior an area of concern for you or your family member?

Sensory Enrichment Therapy™ helps people develop resilience against stress and self-regulation by boosting brain development in these areas.

Join 3,000 families in over 60 countries who have used Sensory Enrichment Therapy™ to help boost brain development in their own homes.

References

- White D, Diana The Sensory Toolbox. Simple 3-Step After-School Routine to Avoid After-School Meltdowns. In: Autistic Mama [Internet]. 17 Oct 2018 [cited 29 Aug 2019]. Available: https://autisticmama.com/simple-3-step-after-school-routine-to-avoid-after-school-meltdowns/

- Chang Y-S, Owen JP, Desai SS, Hill SS, Arnett AB, Harris J, et al. Autism and sensory processing disorders: shared white matter disruption in sensory pathways but divergent connectivity in social-emotional pathways. PLoS One. 2014;9: e103038.

- Ben-Sasson A, Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ. Sensory over-responsivity in elementary school: prevalence and social-emotional correlates. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2009;37: 705–716.

- Fisher AV, Godwin KE, Seltman H. Visual environment, attention allocation, and learning in young children: when too much of a good thing may be bad. Psychol Sci. 2014;25: 1362–1370.

- Sainato DM, Strain PS, Lefebvre D, Rapp N. Facilitating transition times with handicapped preschool children: a comparison between peer-mediated and antecedent prompt procedures. J Appl Behav Anal. 1987;20: 285–291.

- Timmins WG. The Chronic Stress Crisis: How Stress Is Destroying Your Health and What You Can Do to Stop It. AuthorHouse; 2008.

- Juster R-P, McEwen BS. Sleep and chronic stress: new directions for allostatic load research [Internet]. Sleep Medicine. 2015. pp. 7–8. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2014.07.029

- Office APAPIAMRPA, American Psychological Association; Public Information and Media Relations; Public Affairs Office. Chronic Exposure to Stress Hormone Causes Anxious Behavior in Mice, Confirming the Mechanism by Which Long-Term Stress Can Lead to Mood Disorders [Internet]. PsycEXTRA Dataset. 2006. doi:10.1037/e501452006-001

- Bhagat B. Effect of chronic cold stress on catecholamine levels in rat brain [Internet]. Psychopharmacologia. 1969. pp. 1–4. doi:10.1007/bf00405250

- How chronic stress induces insulin resistance, diabetes [Internet]. Nature India. 2015. doi:10.1038/nindia.2015.143

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, Malarkey WB, Sheridan J. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93: 3043–3047.

- Moylan JS, Reid MB. Oxidative stress, chronic disease, and muscle wasting [Internet]. Muscle & Nerve. 2007. pp. 411–429. doi:10.1002/mus.20743

- Al-Zghoul MB, Alliftawi ARS, Saleh KMM, Jaradat ZW. Expression of digestive enzyme and intestinal transporter genes during chronic heat stress in the thermally manipulated broiler chicken. Poult Sci. 2019;98: 4113–4122.

- Xu J, Xu H, Liu Y, He H, Li G. Vanillin-induced amelioration of depression-like behaviors in rats by modulating monoamine neurotransmitters in the brain. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225: 509–514.

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Graham JE, Malarkey WB, Porter K, Lemeshow S, Glaser R. Olfactory influences on mood and autonomic, endocrine, and immune function. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33: 328–339.

- Starcevic, Ana. Chronic Stress and Its Effect on Brain Structure and Connectivity. IGI Global; 2019.

- McEwen BS. Neurobiological and Systemic Effects of Chronic Stress [Internet]. Chronic Stress. 2017. p. 247054701769232. doi:10.1177/2470547017692328

- Davidson J. How to Avoid Brain Aging – Dementia – Memory Loss. JD-Biz Corp Publishing; 2013.

- Blume SR, Padival M, Urban JH, Rosenkranz JA. Disruptive effects of repeated stress on basolateral amygdala neurons and fear behavior across the estrous cycle in rats. Sci Rep. 2019;9: 12292.

- Ballinger S. A comparison of possible effects of acute and chronic stress on post-menopausal urinary oestrogen levels [Internet]. Maturitas. 1981. pp. 107–113. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(81)90002-5

- 6 Benefits of an Uncluttered Space. In: Psychology Today [Internet]. [cited 29 Aug 2019]. Available: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/in-practice/201802/6-benefits-uncluttered-space

- Sanders S. Seizures in Dogs and Cats [Internet]. 2015. doi:10.1002/9781118689691

- Gurney HC, Gurney J. A Simple, Effective Technique for Arresting Canine Epileptic Seizures. Journal of American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association. 2004;22: 19–20.

- Pomares CG, Schirrer J, Abadie V. Analysis of the olfactory capacity of healthy children before language acquisition. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23: 203–207.

- Barinaga M. NEUROBIOLOGY:Mapping Smells in the Brain [Internet]. Science. 1999. p. 508a–508. doi:10.1126/science.285.5427.508a

- Harada H, Tanaka M, Kato T. Brain olfactory activation measured by near-infrared spectroscopy in humans. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120: 638–643.

- Scaglioni S, De Cosmi V, Ciappolino V, Parazzini F, Brambilla P, Agostoni C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours [Internet]. Nutrients. 2018. p. 706. doi:10.3390/nu10060706

- Hongratanaworakit T. Stimulating effect of aromatherapy massage with jasmine oil. Nat Prod Commun. 2010;5: 157–162.

- Cantone E, Ciofalo A, Vodicka J, Iacono V, Mylonakis I, Scarpa B, et al. Pleasantness of olfactory and trigeminal stimulants in different Italian regions. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274: 3907–3913.

- Iannilli E, Sorokowska A, Zhigang Z, Hähner A, Warr J, Hummel T. Source localization of event-related brain activity elicited by food and nonfood odors. Neuroscience. 2015;289: 99–105.

- Diego MA, Jones NA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C, et al. Aromatherapy positively affects mood, EEG patterns of alertness and math computations. Int J Neurosci. 1998;96: 217–224.